The Netherlands

Maurice van Kleef (drums), Coleman Hawkins (sax), Freddy Johnson (piano) (before 1939).

Picture: Collection NJA

During the first years of was Surinam musicians were the only ones allowed to keep on playing jazz. It wasn't exactly prohibited for white musicians but it was restricted. Max Woiski, Lex Vervuurt and Lex van Spall could carry on, because the obtained a declaration of being Arian. ‘Negro-musicians' were in trouble again. These were only small compared to the problems of many jewish musicians, who were completely denied a normal life. Maurice van Kleef was forced during 1941 to play only for jews; he also took part in the revue-orchestra of Westerbork and survived as a member of the camp orchestra. Herman Openneer of the Jazz-archives: ‘Never any Surinam (or Malaysian) musicians were arrested. But it was easier for the more lightly coloured artists, who were regarded as Arian, than for the black musicians’.

The only black musician arrested was the famous pianist Freddy Johnson, because he was an American citizen and therefore from december 1941 considered an ‘enemy’. Dark West-Indians and Malaysians were freed from ‘Arbeitseinsatz’, forced labour in Germany (1942-1944). The nazi’s were afraid ‘racial mixing’. It was also an advantage to swap food and potato coupons for rice coupons. Rice was very much in demand on the black market.

Later on during the war the Germans suggested an exchange between Germans interned in Aruba and Surinam (see: Internment) and West-Indiens in Holland. Many Antillians and Surinames hadn't registered for it. Freddy Johnson was exchanged, from a German camp.

'Kid Dynamite’ (NJA-archief. Picture: Wouter van Goot)

First years

Initially the resistance against Surinam (and ‘Malaysian’) musicians wasn't aimed at the ‘black race’. The occupational authorities only realised later on that some of them weren't Arians. Surinames had a Dutch passport, and the men had compulsary service. They subscribed to the ‘Dutch Kulturkammer’, of which every musician had to be a member - and usually did. Max Woiski sr. still was able to open in 1941 his café La Cubana. For that matter it was quite common to use (Latin-)American artist names like Kid Dynamite, Mike Hidalgo, Lolita Mojica. Woiski called himself Cuban. As an ordinary Surinam person you were considered less.

'Barbaric'

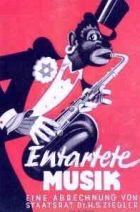

'Degenerate music'. Picture: www.hdbg.de

The resistance against Surinam musicians started because of the ‘degenerate’ or ‘barbaric’ character of their music. In that judgement the black colour of their skin did play a part though. The nazi-sympathizer Amsterdam chief-commisioner Tulp prohibited the café-owners in Januari 1942 to hire Surinam musicians because he thought them to be ‘a great moral danger to the female Dutch youth … young girls feel partly attracted to the black skin and on the other hand partly let themselves be carried away by their barbaric music’.

During this time also a disapproving film about jazz was made with the title ‘Barbarisms’. The Department of Public Guidance and Arts issued in March 1942 a ban on jazz. Author of the text of the ban was jazz-publicist Will G. Gilbert (alias of W.H.A. van Steensel van der Aa). 'The department wants to get rid of 'this primitive negro musical elements in dancing and entertainment music'. The Dutch Kulturkammer had strong colonial views. Surinam negro-musicians were regarded as ‘stowaways’ or ‘deserters’, who liked to ‘dress up as gentlemen’ and actually ‘couldn't do anything else except playing the saxophone’ (Herman Openneer).

Enemy music

Also there were objections to English and, after Pearl Harbour (8 Dec. 1941), American texts and music. During 1942 Dutch musicians were forbidden to use English titles, names for orchestra's of aliases. So ‘Kid Dynamite’ called himself Arthur Parisius again. Still jazz and swing was and stayed popular throughout the whole of Europe. Black gitarist and showman ‘Mike’ Hidalgo first kept his permit after the warning of Tulp, because German military men and members of the Sicherheitsdienst liked to visit the café where he played. Only when a new head of the Kulturkammer arrived all permits for ‘Surinam-negroes’ were revoked (16 October 1943). This wasn't issued by the German authorities.

It was one of the few measures during the occupation on the basis of colour of skin. Mulats from West- and Oost-Indies weren't part of it. Als the possibility remained for non-mixed, say ‘pure of race’ groups to perform. At the end of the war Surinam vrouwen performed in the Colonial Museum as ‘kotto missies’ and a Surinam Indian gave in 1944 dance performances. Herman Openneer: ‘In Augustus 1944 the Kulturkammer complains about musicians still not keeping themselves to the prohibition on jazz- or negro music’.

Names

Max Woiski jr. (NJA-archives)

There were some light-coloured (‘Arian’) Surinam musicians. Most likely they were able to continue working during the entire war: saxophonist, flutist, orchestra leader and composer Max Woiski sr. (1911-1981) and his singing wife Alma Braaf, alias Lolita Mojica. Max, calling himself Cuban, opened during 1941 café ‘La Cubana’, first at the Amstelstraat 43, later at the Leidsestraat. Herman Openneer: ‘People were jalous because of the chances given to Woiski and his wife as ‘Arians’. Black colleagues charged him at the police. He supposedly hid jews, and his wife would prostitute herself’. ‘La Cubana’ just stayed open.

Saxophonist, gitarist and orchestra leader Alexander van Spall (1903-1982). The successful ‘Alex’ van Spall can be regarded as the pionier of the Surinam jazz. Already in 1921 he came to Holland and formed his own orchestra.

Saxophonist, gitarist and orchestra leader Lex Vervuurt (1910-1991). This musician came to Holland in 1934. He told Herman Openneer that during that time in Surinam there was nothing like a jazz-scene.

The black Afro-Surinam musicians formed a special group. Their dark skin soon was a synonym for the ‘negro’ jazz, and they were considered as non-Arians’. Also most of them had no musical education, so they couldn't join the big orchestra's. These musicians (Mike Hidalgo, Teddy Cotton) most of all had a good show. Some others had the quality level for the jazz-business (Parisius, Holtuin). Others will have continued working as long as possible. For one thing their music was popular, also with the Germans.

Saxophonist Lodewijk Rudolf Arthur Parisius (1911-1963) performed as ‘Kid Dynamite’ (Note 1.). He was married to the white Amsterdam Bep Overweg. Parisius developed thanks to his training and study to a good reader of music and therefore also became a composer and arranger.

Drummer Lou Holtuin played with Max Woiski sr. and the American pianist Freddy Johnson. They performed in ‘La Cubana’ by the name ‘Freddy Johnson’s Trio with Lolita Mojica’.

Gitarist and showman Mike Hidalgo. He at least continued playing until October 1943. He was popular with the Germans and sometimes worked together with the Sicherheitsdienst. He tipped them off for prostitutes with veneral diseases.

Trumpet player Teddy Cotton (Theodoor Kantoor). He was good in imitating Louis Armstrong

(picture: www.jazzarchief.nl)

The famous Afro-American pianist Freddy Johnson (New York City, 1904-1961) already performed during the mid thirties in Holland. Togehter with Alex van Spall he played in the ensemble ‘Freddy Johnson & Lex van Spall and their Orchestra’. Herman Openneer: ‘They say that Johnson taught the Dutch how to play the piano’. In ‘Quartet’ with his namen, Mike Hidalgo, Kid Dynamite and drummer Arthur Pay played. De last one was a Hindoustan and born in British Guyana. Another drummer in the Freddy Johnson Quartet was the Amsterdam Antillian Martin Sterman (see below) (note 2.) At the beginning of the war Johnson also had a trio in ‘La Cubana’. Shortly after the attack on Pearl Harbour and the American declaration of war, he was arrested (11 December 1941), like all Americans. Freddy Johnson was interned in Germany (Bavaria) in February 1942 and in March 1944 exchanged for German soldiers in American captivity.

Drummer Martin Sterman was born in Amsterdam as the son of a white mother and an Antillian father (Curaçao). His brother Otto was an actor and recitator, his sister Annie a well known vocalist. They experienced no problems. Annie Sterman performed on 20 July 1944 by the name ‘Topsy’, ‘the West-Indies singer, tap- and rumba-dancer’ in the Waakzaamheid in Koog aan de Zaan, together with well known Zaans' and Westfries' orchestra's and soloists (note 3).

At last there was also a white Surinam active in entertainment music: Ernst Gottfried Bielke (1913), artists name Bruce Low(e). He came to Holland in 1939 and sang negro-spirituals, ’plantation songs’ from Foster and cowboy-songs in German. If needed, he performed with his face painted black.

Rotterdam/Katendrecht*

Kid Dynamite and Teddy Cotton also played in the blooming Rotterdam jazz circuit. Before the war the large dancing Pschorr at the Coolsingel was the most famous place for amusement music, dancing music, swing and jazz. In the city center there were also places like Grand, La Gaité, the Doelen and Atlanta. After the bombardement on the inner city (14 May 1940) the jazz went in hiding in Katendrecht. Also the innkeepers of the bombarded Schiedam Dijk tried the other side.

The old harbour district on a peninsula at the south side of the Meuse used to offer shelter and amusement to Chinese and sailors. There were cafés, prostitutes, gambling dens and opium kits. The danger of venereal diseases and drugs addiction made the German authorities to declare the district prohibited for German military. At the entrances across land and water signs were erected: Prohibited for German soldiers (‘Für Wehrmacht verboten’). Which did not mean that German officers not turning up. Also there were Germans who wanted to stop fighting.

Because the ‘Kaap’ ('Cape') became a sort of free state. Jazz was mostly played in Club Belvedère, the business of Peter Troost and a companion. There were Surinam waiters, a Surinam cloakroom lady and also black porters. Kid Dynamite and Teddy Cotton played there, together with the Rotterdam percussionist Dick Reinooy. Musicians from The Hague played there, and students who joined it with their sax or trumpet. The Surinam cook, Jacky Blue, now and then played drums, just like son Daan Troost. ‘Entartete’ music, surely, but permitted for the considered inferior black race.

In November 1943 finally, there was a raid in the district. Son Daan Troost managed just in time to warn two Jewish persons in hiding, who worked at the Belvedère. A man of the Cultuurkamer ('Kulturkammer'), who headed for the forbidden American music, failed to pay attention to this. Peter Troost, Kid Dynamite and Teddy Cotton were arrested, Teddy being beaten up. But the Surinam musicians soon returned. Daan thinks they had an excuse like ‘We've been exploited by these people for 360 years. Do you really think we hold anything against you?’. But Club Belvédère was to close and after the invasion in Normandy in June 1944 it was over with the jazz music.

*Based on the VPRO tv-programme Andere Tijden of 29 April 2010

On the website 'Het Geheugen van Nederland' a song by Jaap van de Merwe is inserted, where he praises the Belvédère in Katendrecht with 'Cotton & Dynamite' (www.geheugenvannederland.nl).

Notes

1. Herman Openneer (Dutch Jazz-archive) ‘He wasn't a boxer, like the persistent rumour tells’ (see Ad van den Oord, Allochtonen van nu en de oorlog van toen, p. 57)

2. See picture at Ad van den Oord p. 58. According to Herman Openneer from the Jazz-archive the picture was taken in the Broadway Club at the Rembrandt square, not in the Savoy Bar at the Amstelstraat.

3. NJA Bulletin nr. 14, December 1944, p. 34

Sources / More reading

Dutch Jazz-archive (NJA): www.jazzarchief.nl

NJA-Bulletin; information by Herman Openneer, employee NJA

Pictures: Collection NJA

Please do feel free to comment on our English translation. We welcome any improvement!